what term did the us census bureau use to classify

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 21,227,906 [1] 6.6% of the United states of america population in 2017 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Southern United states of america and Midwestern Usa | |

| Languages | |

| English (American English dialects) | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity (Mainly Protestantism) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| American ancestries |

American ancestry refers to people in the United States who self-place their ancestral origin or descent every bit "American," rather than the more common officially recognized racial and indigenous groups that brand upwards the bulk of the American people.[2] [three] [four] The majority of these respondents are visibly White Americans, who either simply utilize this response as a political statement or are far removed from and no longer self-identify with their original ethnic ancestral origins.[v] [6] The latter response is attributed to a multitude of generational distance from bequeathed lineages,[3] [seven] [8] and these tend be Anglo Americans,[7] of Scotch-Irish, English, or other British ancestries, as demographers take observed that those ancestries tend to be recently undercounted in U.Due south. Census Bureau American Customs Survey ancestry self-reporting estimates.[9] [10] Although U.S. Census data indicates "American ancestry" is virtually ordinarily cocky-reported in the Deep S, the Upland South, and Appalachia,[eleven] [12] a far greater number of Americans and expatriates equate their nationality non with ancestry, race, or ethnicity, simply rather with citizenship and allegiance.[13] [eight]

Historical reference [edit]

The earliest attested use of the term "American" to identify an ancestral or cultural identity dates to the tardily 1500s, with the term signifying "the ethnic peoples discovered in the Western Hemisphere by Europeans."[14] In the following century, the term "American" was extended equally a reference to colonists of European descent.[xiv] The Oxford English language Dictionary identifies this secondary pregnant as "historical" and states that the term "American" today "importantly [ways] a native (birthright) or citizen of the United States."[14]

President Theodore Roosevelt asserted that an "American race" had been formed on the American frontier, one distinct from other indigenous groups, such as the Anglo-Saxons.[xv] : 78, 131 He believed "The conquest and settlement by the whites of the Indian lands was necessary to the greatness of the race...."[15] : 78 "We are making a new race, a new type, in this state."[15] Roosevelt'due south "race" beliefs were non unique in the 19th and early on 20th century.[16] [17] [18] [19] Professor Eric Kaufmann has suggested that American nativism has been explained primarily in psychological and economical terms to the neglect of a crucial cultural and ethnic dimension. Kauffman contends American nativism cannot be understood without reference to the theorem of the historic period that an "American" national ethnic group had taken shape prior to the large-calibration immigration of the mid-19th century.[18]

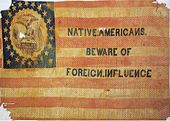

Nativism gained its proper noun from the "Native American" parties of the 1840s and 1850s.[twenty] [21] In this context, "Native" does not hateful indigenous or American Indian, simply rather those descended from the inhabitants of the original Thirteen Colonies (Colonial American beginnings).[22] [23] [18] These "One-time Stock Americans," primarily English Protestants, saw Catholic immigrants as a threat to traditional American republican values, as they were loyal to the papacy.[24] [25]

Nativist outbursts occurred in the Northeast from the 1830s to the 1850s, primarily in response to a surge of Cosmic immigration.[26] The Society of United American Mechanics was founded every bit a nativist fraternity, following the Philadelphia nativist riots of the preceding spring and summer, in Dec 1844.[27] The New York City anti-Irish, anti-German, and anti-Catholic clandestine society the Order of the Star Spangled Imprint was formed in 1848.[28] Popularised nativist movements included the Know Null or American Party of the 1850s and the Clearing Restriction League of the 1890s.[29] Nativism would eventually influence Congress;[30] in 1924, legislation limiting immigration from Southern and Eastern European countries was ratified, as well quantifying previous formal and breezy anti-Asian previsions, such every bit the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Gentlemen'south Agreement of 1907.[31] [32]

Modern usage [edit]

Statistical data [edit]

According to U.S. Census Bureau; "Ancestry refers to a person'due south indigenous origin or descent, 'roots,' or heritage, or the place of birth of the person or the person's parents or ancestors before their arrival in the United States."[33]

Co-ordinate to 2000 U.Due south demography data, an increasing number of United states citizens identify merely as "American" on the question of ancestry.[34] [35] [36] The Census Bureau reports the number of people in the United States who reported "American" and no other ancestry increased from 12.4 million in 1990 to twenty.2 million in 2000.[37] This increase represents the largest numerical growth of any ethnic group in the United States during the 1990s.[2] The state with the largest increase over the by 2 demography was Texas, where in 2000, over i.5 million residents reported having "American beginnings."[38]

In the 1980 census, 26% of United states of america residents cited that they were of English beginnings, making them the largest grouping at the time.[39] In the 2000 Usa Demography, half-dozen.ix% of the American population chose to self-identify itself as having "American ancestry."[2] The iv states in which a plurality of the population reported American ancestry were Arkansas (15.7%), Kentucky (20.7%), Tennessee (17.3%), and Due west Virginia (18.7%).[37] Sizable percentages of the populations of Alabama (16.eight%), Mississippi (14.0%), North Carolina (13.7%), South Carolina (xiii.7%), Georgia (thirteen.3%), and Indiana (11.8%) also reported American ancestry.[40]

Map showing areas in reddish with high concentration of people who self-report as having "American" beginnings in 2000

In the Southern United States equally a whole, 11.2% reported "American" ancestry, second but to African American. American was the quaternary near common beginnings reported in the Midwest (half-dozen.5%) and West (4.1%). All Southern states except for Delaware, Maryland, Florida, and Texas reported 10% or more American, but outside the S, only Missouri and Indiana did so. American was 1 of the top v ancestries reported in all Southern states except for Delaware, in four Midwestern states adjoining the Southward (Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, and Ohio) as well every bit Iowa, and in six Northwestern states (Colorado, Idaho, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming), but only 1 Northeastern state, Maine. The pattern of areas with high levels of American is similar to that of areas with high levels of not reporting whatever national beginnings.[40]

In the 2014 American Customs Survey, German Americans (14.4%), Irish Americans (10.4%), English Americans (7.6%), and Italian Americans (5.4%) were the four largest cocky-reported European ancestry groups in the United States, forming 37.8% of the full population.[41] However, English language, Scotch-Irish, and British American demography is considered to be seriously undercounted, equally the six.9% of U.S. Demography respondents who self-report and identify simply as "American" are primarily of these ancestries.[9] [10]

Academic analysis [edit]

Reynolds Farley writes that "we may at present be in an era of optional ethnicity, in which no simple demography question volition distinguish those who identify strongly with a specific European group from those who written report symbolic or imagined ethnicity."[34]

Stanley Lieberson and Mary C. Waters write "As whites become increasingly afar in generations and fourth dimension from their immigrant ancestors, the tendency to distort, or call up selectively, one's ethnic origins increases.... [E]thnic categories are social phenomena that over the long run are constantly being redefined and reformulated."[36] [42] Mary C. Waters contends that white Americans of European origin are afforded a broad range of choice: "In a sense, they are constantly given an actual choice—they tin can either place themselves with their ethnic ancestry or they tin 'melt' into the wider society and call themselves American."[43]

Professors Anthony Daniel Perez and Charles Hirschman write "European national origins are still common among whites—almost 3 of 5 whites proper name one or more European countries in response to the ancestry question. ... However, a significant share of whites respond that they are but "American" or go out the ancestry question blank on their census forms. Ethnicity is receding from the consciousness of many white Americans. Considering national origins practice non count for very much in gimmicky America, many whites are content with a simplified Americanized racial identity. The loss of specific ancestral attachments among many white Americans also results from loftier patterns of intermarriage and ethnic blending among whites of dissimilar European stocks."[8]

Run across likewise [edit]

- 19th-century Anglo-Saxonism

- A History of the English language-Speaking Peoples

- Albion's Seed

- American English

- American ethnicity

- American gentry

- Americanism (ideology)

- Americans or American people

- Anglo America

- Anglo-Americans

- Anglo-Celtic Australian

- Anglosphere

- Boston Brahmin

- Boston Brahmins

- British American

- Colonial families of Maryland

- Demographic history of the United States

- English (indigenous grouping)

- English language American

- English Americans

- English language colonial empire

- English diaspora

- European American

- First Families of Virginia

- German Palatines

- Henry Hudson

- Historical racial and ethnic demographics of the U.s.a.

- History of the Puritans in North America

- Immigration to the United States

- Jamestown, Virginia

- Maps of American ancestries

- Mayflower

- Old Stock Americans

- Patriot (American Revolution)

- Pennsylvania Dutch

- Pilgrims

- Plymouth colony

- Puritans

- Roanoke Colony

- Roger Williams

- Scotch-Irish American

- Scots Irish

- Scottish American

- Ulster Scots

- Anglo-American relations

- Virginia Visitor

- Welsh American

- White Anglo-Saxon Protestant

- White Southerners

- Who Are Nosotros? The Challenges to America's National Identity

- William Penn

- Yankee

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ a b c Ancestry: 2000 2004, p. 3

- ^ a b Jack Citrin; David O. Sears (2014). American Identity and the Politics of Multiculturalism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 153–159. ISBN978-0-521-82883-three.

- ^ Garrick Bailey; James Peoples (2013). Essentials of Cultural Anthropology. Cengage Learning. p. 215. ISBN978-i-285-41555-0.

- ^ Kazimierz J. Zaniewski; Ballad J. Rosen (1998). The Atlas of Ethnic Diversity in Wisconsin. Univ. of Wisconsin Press. pp. 65–69. ISBN978-0-299-16070-viii.

- ^ Liz O'Connor, Gus Lubin and Dina Specto (2013). "The Largest Beginnings Groups in the United States - Business organization Insider". Businessinsider.com . Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ a b Jan Harold Brunvand (2006). American Sociology: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 54. ISBN978-one-135-57878-7.

- ^ a b c Perez AD, Hirschman C. "The Changing Racial and Ethnic Composition of the US Population: Emerging American Identities". Population and Development Review. 2009;35(one):1-51. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2009.00260.x.

- ^ a b Dominic Pulera (2004). Sharing the Dream: White Males in Multicultural America. A&C Black. pp. 57–60. ISBN978-0-8264-1643-viii.

- ^ a b Elliott Robert Barkan (2013). Immigrants in American History: Arrival, Adaptation, and Integration. ABC-CLIO. pp. 791–. ISBN978-1-59884-219-7.

- ^ Beginnings: 2000 2004, p. 6

- ^ Celeste Ray (Feb 1, 2014). The New Encyclopedia of Southern Civilisation: Volume 6: Ethnicity. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 19–. ISBN978-ane-4696-1658-2.

- ^ Petersen, William; Novak, Michael; Gleason, Philip (1982). Concepts of Ethnicity. Harvard Academy Press. p. 62. ISBN9780674157262.

To be or to become an American, a person did not have to be of any particular national, linguistic, religious, or ethnic background. All he had to do was to commit himself to the political credo centered on the abstract ideals of freedom, equality, and republicanism. Thus the universalist ideological character of American nationality meant that it was open to anyone who willed to become an American.

- ^ a b c "American, northward. and adj." (PDF). Oxford English Lexicon. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c Thomas G. Dyer (1992). Theodore Roosevelt and the Idea of Race. LSU Press. ISBN978-0-8071-1808-5.

- ^ Reginald Horsman (2009). Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism. Harvard University Press. pp. 302–304. ISBN978-0-674-03877-6.

- ^ John Higham (2002). Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860-1925 . Rutgers University Press. pp. 133–136. ISBN978-0-8135-3123-half-dozen.

- ^ a b c Kaufmann, E. P. (1999). "American Exceptionalism Reconsidered: Anglo-Saxon Ethnogenesis in the "Universal" Nation, 1776–1850" (PDF). Journal of American Studies. 33 (3): 437–57. doi:10.1017/S0021875899006180. JSTOR 27556685.

In the case of the United states of america, the national ethnic grouping was Anglo-American Protestant ("American"). This was the first European grouping to "imagine" the territory of the U.s. equally its homeland and trace its genealogy back to New World colonists who rebelled against their mother country. In its mind, the American nation-land, its land, its history, its mission and its Anglo-American people were woven into one groovy tapestry of the imagination. This social construction considered the U.s.a. to be founded by the "Americans", who thereby had title to the land and the mandate to mould the nation (and any immigrants who might enter it) in their ain Anglo-Saxon, Protestant cocky-prototype.

- ^ Tyler Anbinder; Tyler Gregory Anbinder (1992). Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s. Oxford University Printing. p. 107. ISBN978-0-nineteen-507233-iv.

- ^ David Thousand. Kennedy; Lizabeth Cohen; Mel Piehl (2017). The Brief American Pageant: A History of the Commonwealth. Cengage Learning. pp. 218–220. ISBN978-1-285-19329-8.

- ^ Ralph Young (2015). Dissent: The History of an American Thought. NYU Press. pp. 268–270. ISBN978-ane-4798-1452-7.

- ^ Katie Oxx (2013). The Nativist Movement in America: Religious Conflict in the 19th Century. Routledge. p. 88. ISBN978-one-136-17603-6.

- ^ Russell Andrew Kazal (2004). Becoming Old Stock: The Paradox of German language-American Identity. Princeton Academy Press. p. 122. ISBN0-691-05015-5.

- ^ Mary Ellen Snodgrass (2015). The Civil War Era and Reconstruction: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural and Economic History. Routledge. p. 130. ISBN978-ane-317-45791-six.

The upsurge of the faithful fueled bigotry among Americans who demonized cities and discounted foreigners, especially Catholics and Jews, equally true citizens. Old stock American nativists feared that "papists"...

- ^ Andrew Robertson (2010). Encyclopedia of U.S. Political History. SAGE. p. aa266. ISBN978-0-87289-320-vii.

- ^ Larry Ceplair (2011). Anti-communism in Twentieth-century America: A Disquisitional History. ABC-CLIO. p. xi. ISBN978-ane-4408-0047-4.

- ^ Katie Oxx (2013). The Nativist Movement in America: Religious Conflict in the 19th Century. Routledge. p. 87. ISBN978-i-136-17603-6.

- ^ Tyler Anbinder (1992). Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s. Oxford University Press. p. xx. ISBN978-0-xix-508922-half-dozen.

- ^ Tyler Anbinder (1992). Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s. Oxford Academy Press. pp. 59 (note 18). ISBN978-0-19-508922-half-dozen.

- ^ Tyler Anbinder (1992). Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850's. Oxford University Press. p. 272. ISBN978-0-xix-508922-6.

- ^ Greg Robinson (2009). A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in Due north America . Columbia University Printing. p. 22. ISBN978-0-231-52012-six.

- ^ Michael Green; Scott 50. Stabler Ph.D. (2015). Ideas and Movements that Shaped America: From the Pecker of Rights to "Occupy Wall Street". ABC-CLIO. p. 714. ISBN978-one-61069-252-6.

- ^ Kenneth Prewitt (2013). What Is "Your" Race?: The Census and Our Flawed Efforts to Classify Americans. Princeton University Press. p. 177. ISBN978-ane-4008-4679-5.

- ^ a b Farley, Reynolds (1991). "The New Demography Question near Ancestry: What Did It Tell Us?". Census. 28 (iii): 411–429. doi:10.2307/2061465. JSTOR 2061465. PMID 1936376. S2CID 41503995.

- ^ Lieberson, Stanley; Santi, Lawrence (1985). "The Utilise of Nativity Data to Gauge Ethnic Characteristics and Patterns". Social Scientific discipline Inquiry. 14 (1): 44–46. doi:10.1016/0049-089X(85)90011-0.

- ^ a b Lieberson, Stanley & Waters, Mary C. (1986). "Ethnic Groups in Flux: The Irresolute Ethnic Responses of American Whites". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 487 (79): 82–86. doi:10.1177/0002716286487001004. S2CID 60711423.

- ^ a b Ancestry: 2000 2004, p. 7

- ^ Celeste Ray (2014). The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume six: Ethnicity. University of N Carolina Press. p. 19. ISBN978-1-4696-1658-2.

- ^ "Ancestry of the Population past State: 1980 - Table 3" (PDF). Census.gov. 2017.

- ^ a b Demography Atlas of the Usa (2013). "Ancestry" (PDF) . Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- ^ "Selected Social Characteristics in the United States (DP02): 2014 American Community Survey one-Twelvemonth Estimates". U.South. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on Feb fourteen, 2020. Retrieved Nov x, 2016.

- ^ Lieberson, Stanley (1985). "The Use of Nativity Data to Estimate Ethnic Characteristics and Patterns". Social Scientific discipline Research. 14 (1): 44–46. doi:ten.1016/0049-089X(85)90011-0.

- ^ Waters, Mary C. (1990). Indigenous Options: Choosing Identities in America . University of California Press. p. 52. ISBN978-0-520-07083-vii.

Sources [edit]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_ancestry

0 Response to "what term did the us census bureau use to classify"

Post a Comment